Bank of England must not cut rates this week

- Latest forward-looking indicators are positive so using pre-election economic weakness to justify rate reductions makes no sense .

- Who will benefit from lower interest rates anyway? Mortgages may be cheaper but house prices and rents may rise, and banks have not passed on rate reductions to consumers.

- Higher credit card and overdraft rates and more consumers using buy now pay later schemes are weakening household finances.

Apparently there is talk of the Bank of England deciding to reduce interest rates at its meeting this week. It is difficult to fathom the economic rationale for such a move. Rates are already at emergency levels, having been stuck close to zero and well below inflation for over ten years. The usual rationale for lowering rates is to revive growth during an economic slowdown, or to anticipate future weakness if leading indicators have weakened. But the UK economy has been showing clear signs of recovery after pre-election weakness at the end of last year, not ongoing weakness.

Pre-election fears have given way to positive economic indicators: With the emphatic Conservative General Election victory, prior fears of a Marxist Labour Government in charge of the economy and possible imminent No Deal Brexit have disappeared. Those uncertainties had obviously held back spending and investment, but the Purchasing Managers Indices, UK capital markets and house prices have recovered well since mid-December. Consumer spending and household borrowing have risen, despite low interest rates, as savings incentives are so weak when interest rates remain well below inflation and families struggle with the rising cost of living.

Monetary policy should not be backward-looking: Cutting rates would mean policymakers responding to lagging indicators that represent circumstances which have fundamentally changed. Normally, monetary policy should be prudently set to reflect future developments. Of course, it is possible that leaving the EU will see further uncertainties later this year, but it is far too early to predict this now – and indeed policy is already extremely accommodative.

Monetary policy is still in emergency mode as dangers of ultra-low rates seem underestimated: The Bank of England is still buying gilts to maintain its Quantitative Easing programme. As the bonds it has bought mature, it purchases more to replace them, which has maintained downward pressure on gilt yields. Indeed, the ultra-low interest rate environment has itself distorted asset markets in ways we do not yet understand. Gilts are supposedly the ‘risk-free’ rate that all other assets are priced against, but gilt prices have been impacted by QE. The Capital Asset Pricing Model underpins capital markets, making normal asset risk models less reliable. With such low (or in some countries negative) returns on ‘safe’ assets, many investors are being driven to take on new risks, in order to try to achieve decent returns. This is transferring default risks from banks onto other institutional or private investors.

‘Money-Tree Policy’ is like easing fiscal policy without political accountability: I do fear that the Bank of England’s monetary policy (‘Money-Tree Policy’) is storing up problems for the future. Quantitative Easing (money-printing by another name) was a huge monetary experiment, designed as an emergency boost when the debt bubbles caused by irresponsible lending burst. It was never meant as a permanent reflation mechanism once the emergency economic situation has passed. It has benefited the most powerful groups and the wealthiest citizens. Policymakers, Governments and financial markets have benefitted enormously from this policy and may have become ‘addicted’ to ongoing easing. Central banks have used monetary policy to replace fiscal easing and allow Governments to spend far more than they could have afforded without ultra-low bond yields.

In the meantime, ordinary households face rising risks and rising debts: The vast majority of savers hold their savings in cash, not in assets (they m ay have pension assets but their available disposable savings of 80% of the population are almost all in short-term deposits. Therefore, they have actually been damaged by low interest rates as the real value of their savings falls year by year. If the Bank of England lowers rates this week, it will be inflicting further pain on savers, especially those outside the wealthiest 20% of the country. Those who do have assets have benefitted from the impact of monetary policy in boosting asset prices.

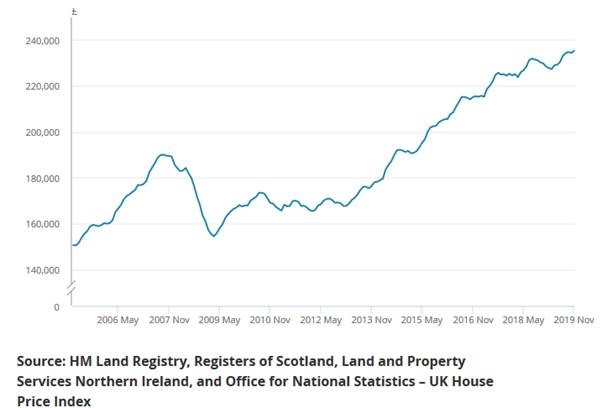

Even cheaper mortgages are not necessarily good for the economy: An oft-cited benefit of lower interest rates is the boost for mortgage borrowers. But this is not an unalloyed positive. Yes, mortgage rates have fallen, but house prices have risen sharply (see chart below) so that new purchasers must borrow more to be able to get on the housing ladder. Overall, the cost of servicing mortgages has fallen for those who already owned their own home. Around two-thirds of UK households own their own home, with 4.5million households (mostly the older generations) having no mortgage. There are 11million households with an outstanding mortgage and they might benefit from lower mortgage interest rates, but they are not the majority of the population.

AVERAGE UK HOUSE PRICES 2005 -2019

Majority of households do not benefit from mortgage rate falls as younger, less well-off groups face rising rents: And other groups have been negatively affected. Rents have risen as house prices have increased, which has hit lower earning and younger people hard. For example, among people aged 25 to 34, 55% are renting their property.

And pension funds are damaged by QE as risk and annuity costs increase: With low bond yields and returns well below inflation, long-term investors cannot prepare for a secure future. They are forced to either accept falling asset values in real terms, or try to find riskier ways of generating returns. By taking on more risk, they may end up better off, but not everyone will. And if the debt problems become even larger, there could be a loss of confidence that hits markets again. And the cost of buying secure pensions has spiralled as annuity rates fall when gilt yields fall.

Credit card and overdraft rates have risen and consumers are enticed into debt or buy now pay later schemes which weaken financial resilience: UK household finances have worsened and household debt has reached record levels, far higher than before the 2008 crisis. Even though interest rates have fallen, credit card interest rates reached a record high last month and the FCA’s latest brainwave for helping customers with unauthorised overdrafts has seen punitive increases in costs of arranged overdrafts for the more responsible customers. In addition, more retailers are encouraging people into buy now pay later purchases, which are leading to rising debt problems. Retailers have started to become credit companies, with significantly increasing proportions of their profits coming from consumer loans, rather than goods sold. With interest rates near zero, consumer credit rates are still above pre-crash levels. (See chart below). Regulators have clamped down on mortgage lending but consumer credit has no required checks. Unsolicited credit limit increases, issue of unrequested consumer loans and encouragement to take on more debt for consumer items are all storing up dangers which further rate cuts will not address.

CREDIT CARD INTEREST RATES

Interest rate

Source: Bank of England Household interest rates statistics, table G1.3

I fear that central banks have not recognised the risks their policies entail: Just reducing rates, when they are already so low, is not necessarily a benefit to the economy. Yes, it can help banks and lenders who increase or maintain their margins, but savers, pension funds and ordinary households may well be worse off.

I urge the Bank of England not to cut rates this week.

One thought on “Bank of England must not cut rates this week”

Another excellent commentary Ros.